In the Hokuriku region, there are a variety of festivals that take place throughout the year, some being very orthodox, while others are much more peculiar and unique.

"Aenokoto" – Pleasing the Invisible Field Gods

Japan is an agrarian country, and for a long time, the focus of daily life revolved around a successful harvest. For this reason, throughout the country there are many religious festivals dedicated to the field gods. In the Okunoto region of Ishikawa Prefecture, there is a unique traditional festival called "Aenokoto" where the farmers invite the field gods into their homes after the harvest and show them hospitality.

In contrast to the majority of planting and harvest festivals that are held in a village as a whole, "Aenokoto", which roughly means "festival for entertaining with food and drink", is held independently in each farmer's home. Although the time and duration of the festival will vary from house to house, in general, the gods are invited into the houses on December 5th and are sent out on February 9th.

"Today is Aenokoto. Thank you for working in and blessing the soil for all this time. I've come to greet you and pick you up. Please come to my home."

On December 5th, farmers don the "kamishimo" (a ceremonial dress from the Edo Period) and treat the invisible field gods as real guests and guide them to their homes. They believe the gods have hurt their eyes on the ears of rice, so on the way home they occasionally say phrases like, "Please, mind your step." After arriving, they invite the gods to a bath, and then offer them a banquet, explaining each dish.

These gods usually reside in the inner rooms of the house, spending New Year's Day with the family and staying until February, when they return to the rice fields. This act of serving an invisible god might seem very strange to contemporary people, but even so, the sincerity of their hearts cannot be doubted. That is the message that Aenokoto sends to us.

Treatment of the Gods Varies From Region to Region

The mikoshi, a portable shrine, is considered to be a god's method of transportation, so in most cases, they are very carefully treated. However, in the Abare Festival, roughly translated as "Violence Festival", held in July every year at Yasaka Shrine (in Ushitsu, Ishikawa Prefecture), the mikoshi is violently handled, and in the end, it is completely destroyed.

The origin of Abare Festival dates back to a long time ago, when a terrible sickness ravaged the area. At that time, the god of Gion was invited from Kyoto and a great festival was held. Two mikoshi and several kiriko (lantern floats) paraded through the town streets from early in the morning to late at night. On the last day, the mikoshi was thrown repeatedly into the sea and river, then set on fire for people to dance and romp around.

Most people would imagine that a god would get angry at being so roughly treated. However, the people here believe that the god calms down after having rampaged to his / her heart's content. It is like a kind of stress release.

The Abare Festival takes place every year in the Ushitsu District of Noto Town on the first Friday and Saturday of July

In Jōnichiji Temple in Himi City, Toyama Prefecture, there is a festival called the Gongon Festival, where many brave men carry huge logs weighing several dozen kilograms and compete to see how many times they can strike a bell in one minute. The origin of the Gongon Festival dates back to the Edo Period, when farmers prayed to the gods for rain during a severe drought. When it finally rained, the farmers expressed their joy by striking bells.

In Kamo Temple in Imizu City, Toyama Prefecture, there is a ritual called "Buriwake Shinji", held during the New Year, where yellowtail fish offered up by the local people are divided and distributed to the parishioners' homes. Yellowtail is called by different names at different stages of its growth. This festival is celebrated to pray for good health throughout the year.

(Left, Top Right) Strong men from throughout the prefecture participate in the Gongon Festival, trying to see how many times they can strike the bell with a log in one minute. (Bottom Right) On New Year's Day, the Buriwake Ritual takes place at Kamo Shrine. After the ritual is over, the yellowtail fish is cut up and distributed with rice cakes to the parishioners.

A variety of festivals that reflect the local history and culture

In February in Echizen City, Fukui Prefecture there is an event called "Gobō-kō" where people eat a lot of gobō (burdock root) to pray for a good harvest. This tradition began a long time ago, when the people suffered from paying heavy land taxes. They would cultivate secret crops, and once a year have a celebration where they would get full on gobō.

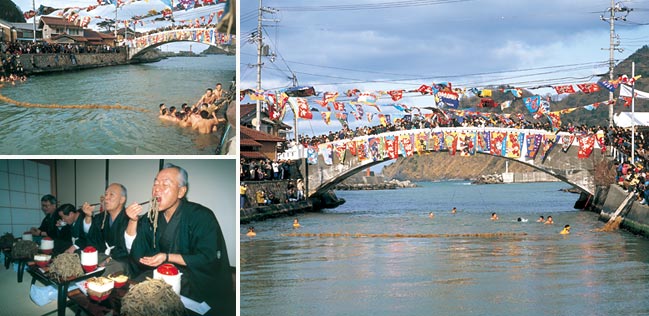

In Mihama Town, Fukui Prefecture, an event called "Hiruga Water Tug-of-War" is held every January. In this competition, young men wearing only loincloths compete to see how fast they can pull apart a thick rope. This event originated from a custom of predicting the fish harvest for the whole year through a competition of tug-of-war. Usually the town is very quiet, but on this day, it is filled with an atmosphere of excitement.

On January 15, in the middle of winter, young men dressed only in loincloths jump into the water in a competition to see who can most quickly pull and break apart a piece of rope 40 m long and 30 cm thick. This festival has a history of 300 years (top left, right). During the Gobō-kō event, men dress up in hakama (traditional formal dress for men) and eat gobō (burdock root) with rice and drink sake until they are full(bottom left).

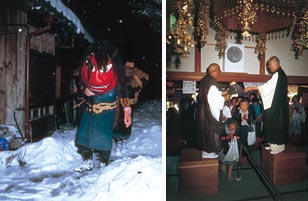

(Left) On the 15th night of the first month of the lunar calendar, the "Appossha" enters houses in the Koshino District of Fukui City with a low growl, banging on the lids of kettles in an attempt to scare poorly behaved children into behaving well. "Appossha" means "I want mochi" in the local dialect. (Right) From June 30th to July 1st, at Hōunji Temple in Obama City, Fukui Prefecture, monks turn a mortar upside down and burn mugwort herbs on top. Worshipers then pass underneath the overturned mortar to ward off diseases and palsy.

In the Hokuriku area, there is a great variety of unique festivals that reflect local history and culture. Throughout Japan, many festivals face the threat of extinction due to depopulation and the aging of society. However, in the Hokuriku area, even though times may change, the culture of festivals is firmly rooted in the peoples' daily lives, and it is passed down from generation to generation by those who love their hometowns.

If you are looking for unique festivals full of laughter, warmth, and power, definitely take a trip to Hokuriku.

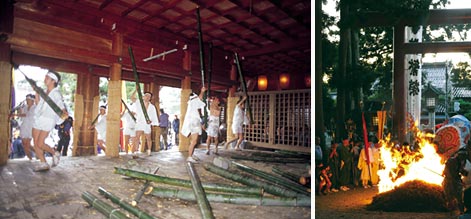

(Left) Every February at Sugōisobe Shrine in Kaga City, Ishikawa Prefecture, young men dressed in white try to smash 200 green bamboo logs on the stone pavement. (Right) Every September at Kushida Shrine in Imizu City, Toyama Prefecture, there is an autumn festival where lion dancers and a mikoshi (portable shrine) run through fire.